Security Spending in Insecure Times

See The Simons Foundation Canada's page on Canadian Defence Policy for briefing papers by Ernie Regehr, O.C., Senior Fellow in Arctic Security and Defence at The Simons Foundation Canada.

Security Spending in Insecure Times

Canada and all of NATO are necessarily rethinking their security postures in response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, with all its ensuing horrors. But the haste with which NATO has come to focus on increasing military spending, in an already heavily armed alliance, ignores the centrality of non-military security measures. Peacebuilding and diplomacy, both seriously under-funded, are key to ending and preventing wars, and for building the conditions for sustainable peace.

Pundits and editorialists have delivered a near-unanimous verdict – that Canadian and NATO military spending has been woefully inadequate in the face of Russian aggression, and that now is the time to do something about it. According to this readily formed consensus, “doing something” is defined as committing to major long-term military spending increases. But the inconvenient truth is that the numbers don’t back up this familiar and now reinvigorated conventional wisdom. NATO military spending already surpasses that of Russia many times over. And, as for Canada, it is still and consistently has been within the top fifth of NATO’s 30 members in absolute military spending. Furthermore, the extraordinary destructiveness of modern warfare, once again on tragic display, should remind us of the Mikhail Gorbachev dictum that the essential role of modern military forces must be to prevent, not “win,” wars. Military forces certainly need to be properly funded and equipped for war prevention, but so too do peacebuilding and diplomacy.

NATO vs Russian military spending and capacity

NATO’s own reporting puts the collective military spending of its 30 member states at US$1.106 trillion in 2020, and an estimated $1.174 trillion for 2021. NATO arrives at those totals by converting figures reported by member states in their respective currencies into US$ at current exchange rates. Russian military spending is calculated in the same way by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), and it places Russia’s 2020 military spending at the equivalent of $66.8 billion – in other words, at 6 percent of NATO spending. Stated another way, by those measures NATO members collectively spend at least 16 times as much as Russia does on military preparedness.

Of course, it’s not quite as simple or stark as that. Analysts, including those at SIPRI, point out that such spending comparisons are not necessarily a reliable measure of respective military capacity. How that money is spent (for example, relative spending on personnel, equipment/weapons, research and development, and so on) makes a difference. Past rates of spending are also relevant for assessing the comparative capacities in accumulated arsenals. In Russia’s case, some Western analysts find it useful to also use a “purchasing power parity” (PPP) measure instead of a straightforward currency conversion, factoring in Russia’s ability to purchase military goods and services domestically on much more advantageous terms using its own currency. Similar PPP rates for military spending in NATO states are not available for direct comparison with Russian spending, but SIPRI points out that “there are strong indications that military goods and services cost less in Russia than in the USA or most of Europe.” Thus, the International Monetary Fund calculates Russian military spending power at the equivalent of about US$167 billion (rather than $66.8 billion) in 2020. But that still amounts to only about 15 percent of NATO spending. Of course, not all of the military capacity of NATO states, notably the US and Canada, is focused on European defence, but neither is all of Russia’s military capacity available for its European flank.

Is Canada a military laggard?

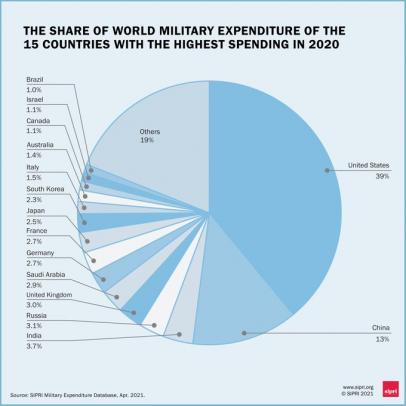

Portrayals of Canada as a defence spending laggard are ubiquitous, but, again, NATO numbers do not support that dominant narrative. Canada’s 2021 defence expenditures, according to NATO counting criteria, reached US$26.5 billion – that is the sixth highest in absolute military spending among NATO members (just within NATO’s top 20 percent). NATO includes items in defence spending that are not included in Canada’s own numbers, but that counting methodology applies across all members, so the numbers and ranking comparisons stand – and those are not the numbers of a laggard. Canada’s own numbers in the Department of National Defence Main Estimates for 2020-21 are C$23.3 billion. SIPRI ranks Canada at 13th in world in military spending in 2020 – well within the top 10 percent of military spenders world wide (where Canada has long ranked). The Canada-as-laggard school of commentary doesn’t challenge those numbers, it just ignores them, focusing instead on Canadian defence spending as a percentage of GDP – which, at 1.4 percent, does indeed currently put Canada at fourth from the bottom in NATO.

There are long-standing proposals to peg both military and development spending to consistent percentages of GDP as a way of ensuring ongoing funding increases. The pledge of NATO states to “aim to move towards the 2 percent guideline” is well known. It was first formalized in 2006, but by 2021 fewer than a third of NATO states had met that goal – and in the spirit of not wasting a crisis, NATO is keen to use this one to add new pressure, even though the alliance already outstrips all competitors. For Canada to meet the 2 percent target would require a minimum of another $12 billion annually.

A parallel spending formula is the UN’s 1970 proposal that the world’s more prosperous states peg their official development assistance (ODA) to at least .7 percent of gross national income (GNI). The Development Assistance Committee of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) consists of 30 donor states, and only six have to date reached or surpassed the .7 percent target (the UK, Germany, Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden), the latter three with ODA budgets at more than 1 percent of GNI. In 2020 Canadian ODA was just under US$5 billion in absolute spending (as calculated by OECD), or .31 percent of GNI. Canada ranks 9th highest of the 30 OECD donor states in absolute spending (just making it into the top one-third), and ranks 14th highest in percentage of GNI (just making it into the top half). The Canadian ODA budget would obviously have to more than double for Canada to reach the .7 percent target and to make Canada a more serious development and peacebuilding presence.

Linking defence and ODA spending levels to national wealth invokes an ability-to-pay principle, which makes good sense when it comes to development assistance, but there is considerably less logic to linking defence spending to national wealth. Inasmuch as ODA is a wealth transfer mechanism (roughly analogous to Canada’s inter-provincial equalization payments), the link to GDP makes eminent sense. Relative national wealth is a credible, concrete way to establish a state’s financial obligations to the less wealthy of the world. But national defence spending obligations are logically tied to national security requirements, not to wealth and the ability to pay. No state’s national defence requirements rise because its GDP has risen. There is of course an obligation on all states to contribute to international peace and security (which is not the same as an obligation to NATO), and high-income states should be more forthcoming than those with more limited means, but military spending levels should fundamentally be linked to national defence requirements, not wealth levels.

Canada, for example, has a range of enduring defence responsibilities (currently including renewal of the North Warning System), but these are in no way conditioned by the size of our GDP. Monitoring Canadian frontiers and approaches to Canadian air, sea, and land spaces, including in the Arctic, is an ongoing obligation, and the job doesn’t get bigger or smaller, or more or less expensive, just because our GDP rises or, sometimes, declines. The same goes for the military’s responsibility to aid civil authorities in search and rescue and disaster response. Furthermore, in Canada, the near universally accepted threat assessment is still that we face no – or very little — direct military threat. And just as surely as the presence of imminent military threats is expected to increase requirements for military planning and preparedness, and thus costs, so too should the absence of such threats ease requirements and costs. Why would states not facing direct threats choose to spend as much on defence as those under credible threat? Continue reading....

Ernie Regehr, O.C. is Senior Fellow in Arctic Security at The Simons Foundation Canada, and Research Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Conrad Grebel University College, University of Waterloo.